“Find me a place where the river is nice and wide,” Julius Caesar told his tribunes. “And sort of mean.”

“Yessir.”

The “Tusculum portrait”, possibly the only surviving bust of Caesar made during his lifetime (public domain photo)

The “Tusculum portrait”, possibly the only surviving bust of Caesar made during his lifetime (public domain photo)

They came back with a couple of options. Some scholars think Caesar chose a stretch of the river near Cologne, others think it was near Koblenz or Bonn. The Rhine is nearly a quarter of a mile wide at those places and “mean”—with a strong current and a full twenty feet deep. In Caesar’s time there was a thick forest on both banks.

What was he up to?

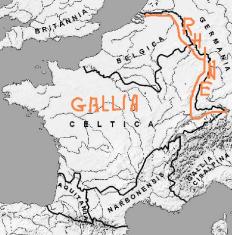

He had decided to go after the Germans (the Germani) on the other side of the river. The Rhine was the border between Germany (the Germani) and France (Gallia). The Germans crossed it and raided Gallia from time to time and they had to be taught never to do that again.

Map of ancient Gaul (file)

Map of ancient Gaul (file)

They had just come over the river and the invaded Gauls had called on Rome to protect them. Caesar went to the rescue and in a fierce battle annihilated a German army and sent the survivors scurrying back across the Rhine. They figured they were safe there and that had to stop.

“Now that he [Caesar writes in the third person] had seen how easily the Germans were induced to invade Gaul, he wanted them to experience fear…when they realized that the army of the Roman people was both capable of crossing the Rhine and brave enough to venture it.” The Germans were not going to be able to hide behind that river anymore—not from Rome.

There were other good reasons to cross. A little tribe called the Ubii, who lived on the other side, were allies of Rome and they had sent word to Caesar that they were being threatened. Could he send some soldiers over to show the Germans that Rome would protect them?

Caesar wanted to punish some tribes that had just fought against him, too, and had escaped across the river.

How was he going to take his army over? With dignity, of course. The Ubii promised to provide boats to ferry his soldiers across but “he was not convinced that such a method of crossing was in accord with either his own dignity or that of the Roman people. So despite the extreme difficulty of the task which lay before him of constructing a bridge (because the river was so broad, swift, and deep), he nevertheless concluded that he must attempt a crossing by bridge—or not take his army across at all.”

He put down the map of the river and picked up the bridge design his engineers had worked out: “ Gentlemen, it is not wide enough.”

They looked puzzled. Their bridge was five whole meters wide—enough to accommodate five fully-armed soldiers marching side-by-side.

“I don’t want a dinky bridge,” Caesar told them, “something that will just do. This bridge is supposed to knock the Germani out. It ought to scare the bastards. It ought to show them the kind of thing Rome can do and will do for her friends and against her enemies. Make it twice as wide. ”

A few hours later the engineers came back with the bridge as wide as a modern two-lane highway.

Caesar nodded at the change but his eye went right to another problem:

“Can’t we do something to protect our piles? When they see what we’re up to, the Germani are going to fill the river with logs, and with a current like that one they’ll knock the devil out of our bridge.”

“We could station men in rafts to intercept the oncoming logs,” said one of the engineers.”

“And a shield of some kind?” said Caesar. “How do you protect a fighting man? With a shield. How might you protect a bridge? With a shield. We could put wedge-shaped fences in front of the piles. Besides deflecting enemy obstacles they would divide the waters and reduce the force of the current on our bridge.”

“Very good, sir.”

Bridge shields (source unknown, 100falcons file)

Bridge shields (source unknown, 100falcons file)

“How long is it going to take us to make this thing?” Caesar asked.

The engineers knew he was in a hurry so to please him they had come up with a nearly impossible deadline for themselves. “Twenty-five days,” they said and held their breath, “including felling the trees and cutting the logs and branches.”

“Oh, come on,” said Caesar. “You men have built dozens of bridges and all the material is right here at hand. This bridge has to go over that river in record time. Let the men work in shifts all night and give them good protection from cavalry. It would be nice if the Germani scouts didn’t even know we meant to build a bridge until we started. How about ten days to gather material and ten days to span the river? If you fellows can’t do it, just say so and we’ll scrap the bridge. Maybe I was wrong about my engineers and what they can do.”

Caesar was a genius at influencing men, making them come his way. This was one of his old tricks. He had used it just after taking command of Gaul when his newly-recruited legions heard they would fight the big, fierce Germans and got scared. There were rumors of mutiny. Caesar addressed them: “I don’t believe you men are cowards or would really let Rome down. But just to see who will do his duty and who won’t, I’m going to break camp tomorrow morning. Anyone who wants to follow me to glory can come along. If the whole bunch of you chicken out I won’t mind. My loyal Tenth Legion and I will face the enemy and do the job by ourselves.” Of course the ashamed soldiers joined him in the morning. Now the engineers were challenged to do the impossible.

In ten days, chopping day and night, the soldiers had the logs and branches ready. And in ten more days they built Caesar his bridge while the unbelieving Germans watched from the other side. Awed. Scared. The Romans were coming after them.

Caesar’s bridge over the Rhine (public domain photo by Lo Scaligero)

When the bridge was finished, Caesar paraded his army across in wide rows, the cavalry first, their horses draped with colorful trappings, then the foot-soldiers, with horns blaring, flags waving, and the near-sacred standards held high in the air. They met no resistance on the other bank. The Germans had fled and were hiding in the forest.

Caesar spent 18 days trying to find the enemy, burning the villages that he saw and razing the corn fields. Then, figuring he had accomplished his mission, he marched back across the dignity bridge.

And tore it down.

Model of Caesar’s bridge across the Rhine (Museo nazionale della civiltà romana, Roma; ©**) courtesy of http://www.livius.org/ra-rn/rhine/rhine.html

Model of Caesar’s bridge across the Rhine (Museo nazionale della civiltà romana, Roma; ©**) courtesy of http://www.livius.org/ra-rn/rhine/rhine.html

This story is taken from Caesar’s own account in his Commentaries (also called The Gallic Wars), Book Four, chapters 16-19. I have used the translation of Carolyn Hammond

Pingback: Donald Trump: A Roman Repeat? – Reiteration

how ceasar be the great mind great minds are engineers who mad that bridge!

Caesar: the greatest mind in the history..

Nice. Thanks for the info.

Thanks a lot, Ritesh Ranjan. Riht now I can’t answer your long and interesting comment as I would like to; but I urge you to read Cicero. More is known about Caesar than about Alexander, mainly because he himself wrote and because the greatest writer of the age, Cicero, who knew him, wrote about him and his dictatorship in exciting letters. Cicero admired him but came to hate him because he gave the coup de grace to the Roman Republic. Look Cicero wrote about him:

“His character was an amalgamation of genius, method, memory, culture, thoroughness, intellect, and industry. His achievements in war, though disastrous for our country, were none the less mighty. After working for many years to become king and autocrat, he surmounted tremendous efforts and perils and achieved his purpose. By entertainments, public works, food-distributions, and banquets, he seduced the ignorant populace; his friends he bound to his allegiance by rewarding them, his enemies by what looked like mercy. By a mixture of intimidation and indulgence, he inculcated in a free community the habit of servitude.”

Fascinating, I must say. I am not a historian, infact, I am a Training & Development professional working for an American MNC in India. However, I’ve been greatly interested in History ever since I studied about Alexander in the sixth grade. I like reading about World History in general and Indian History in particular. Alexander has always captured my imagination and I’ve read 5-6 books on his life and campaigns. I’ll admit though that my knowledge of the life of Julius Caesar is entirely based on Shakespeare’s play and I know he did not write about the historical Caesar. He created a character that in comparison would make Brutus look pious, righteous, and worthy of emulation. Shakespeare’s Caesar was physically weak (epileptic and deaf in the right ear), pompous, and worse, condescending of his friends and colleagues in the senate. However, reading your post I could not help but draw comparisons between Alexander and Caesar. Both were ambitious and brave, both had an appetite for going after the unknown, both had astute military and tactical acumen, both led from the front, both thrived in danger, and both were excellent orators and motivators. Reading about the Dignity Bridge, I recalled Alexander’s campaign against Tyre, when he ordered a bridge to be built on sea to lead to the island nation. The bridge was built in quick time against all odds and was strong enough for the Macedonian army to take their huge battering rams to the city gates. It was more a show of power than anything else. The capture of the Sogdian rock is another such example. And of course, the crossing of the river Hydaspes in the middle of the night in which Alexander almost drowned, to launch a surprise attack on Porus. There are many more and they all cannot be captured in this space here. Yes, Alexander achieved a lot more at a much younger age and Caesar is believed to have cried at Alexander’s grave, saying he had achieved nothing in comparison to what Alexander did by the age of 32. Anyway, I loved this post and hope to read many more on Caesar and Roman History. I like the way you write…its simple and lucid yet powerful.

It’s funny how that whoever wins in politics is not essentially the smart one, but is the one who is an expert at convincing others to do something.

Erika:

Caesar must have been sure that the Germani wouldn’t soon cross back over the river because the next thing he did before winter set in was to hurry over to Britannia.

The Senate voted for an official thanksgiving, not for the bridge as such but for Caesar’s victory over the Germani. His arch-enemy Cato condemned the vote, however, saying that Caesar had acted criminally when he massacred the enemy during a truce.

What happened? Caesar says he had not agreed to any truce and it was the enemy that were treacherous. They tricked him twice and tried a third time by pretending to come to his camp to negotiate. He arrested the envoys and attacked the enemy camp while they weren’t expecting him. He killed all the women and children he could find too. That in itself was nothing criminal to a Roman mind. Roman armies habitually killed whole enemy populations to terrorize or eliminate resistance. What was criminal was the violation of a truce, the breaking of your word of honor. Cato said Caesar should have been turned over to the Germani to punish as they saw fit.

That’s what I call a show of force! I hope that took care of the Germans for a long time. Did it? If it did, he saved loads of money for Rome, for not having to come back to defend the weak borders. Does he say anything about what was the echo of his genius stunt back in Rome?

Very apt title for your great post.

Fascinating, as usual. I especially enjoyed the third picture which gave me an idea of how such a bridge was constructed in ancient times.

Expat 21